Twenty-five years ago today lightning struck the building I slept in. It wasn’t my house—that structure safely sat 405 miles away in St. Louis Park, MN. It was the dormitory of my boarding school, Fasman Yeshiva High School, in Skokie, IL (aka Hebrew Theological College, aka HTC, aka Skokie Yeshiva, aka The Yeshiva). I boarded alongside seventy five or so “out-of-town” high school students, thirty to fifty college students, and a handful of families who lived in apartments in the building.

The building looked like the letter H from overhead. Made of brick, it stood three stories, topped off by a tall chimney. High school dorm rooms lined two of the three hallways on the second floor, each one marked by a numbered plaque stuck to the heavy brown door. Bright beige tiles covered the floors. (We wondered whether or not they were made of asbestos). Walls of glazed cinder block and concrete lined the hallways and dorm rooms, meant to withstand the imaginations of bored teenage males. Each room shared a bathroom with another room and held two-to-three students from small cities across the country that lacked their own Jewish high schools.

It was February 27th, 1999. I was a sophomore and fifteen years old—the age of rebellion. Jenko jeans. Middle hair-parts. Curfew delinquencies. A robust CD collection protected by a black binder contained discs from my favorite artists: Sublime, Metallica, Greed Day, Creed (yes, I’ll admit it), Aerosmith, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and, of course, Tupac. (The Yeshiva only allowed Jewish music in the dorms so this prized possession remained well-hidden in a locked trunk.) I spent most of my free-time listening to music, playing basketball, goofing off with friends, and finding ways to talk to girls on one of the few pay phones without getting caught by dorm counselors.

Dorm counselors enforced the dorm rules. College students with two primary responsibilities: 1. Ensure we were in our rooms at curfew (and stayed there). 2. Wake us up in the morning and get us out of bed in time for prayer services. The power struggle between the two classes of males often reached boiling points. However, as we aged dorm counselors seemed to care less and less about their duties.

My dorm room was at the end of the hall—the last room on the right. Off the grid. Under the radar. Close to the stairwell exit for easy in-and-out access. Both of my roommates lived “in-town” and only stayed in the dorm a few nights a week when we had night classes, so I often had the room to myself. On this Friday night I may have been one of the few people in the entire building sleeping in a room alone.

The holiday of Purim started Monday night, which meant that this weekend (Sabbath/Shabbat) was special. It was Parshat Zachor or the “Portion Of Remembrance.” (Parsha/Portion refers to the Torah portion that is read in synagogue on Shabbat). Purim commemorates a tale of Jewish survival when in 500 BCE a triangular-hat-wearing villain named Haman tried to destroy the Jewish people but failed because Queen Esther and her uncle Mordachai outsmarted him and convinced King Ahasuerus (aka Xerxes) to save the Jews and kill Haman instead.

To commemorate this commemoration, we read Parshat Zachor on the shabbat before Purim and recount the biblical story of when the Amalekite nation tried to kill the Jewish people as they fled slavery in Egypt. (Unfortunately — or fortunately —Jews have a lot of stories and holidays about survival).

I went to sleep Friday night with the implicit understanding that the dorm counselors intended to bring their best efforts to wake-up routines in order to assure our attendance for Parshat Zachor.

The experience of sleeping at age fifteen is nothing like sleeping at age forty. Twenty-five years ago sleep was an all-encompassing endeavor, full of rapid eye movements and detailed dreams. Deep and glorious, uninterrupted by children or worry. Restorative. Pure and delightful. (And to think how much we took it for granted!). It was in this far-off state of consciousness that the initial crash reached my senses. I remember experiencing the boom as I slept; that feeling when reality knocks up against dreams and the two intertwine in some mysterious way. I heard it, and perhaps even felt it, but it didn't wake me. It just became part of the dream in the form of a jet engine overhead or a loud knocking on a door or something of that sort.

“The experience of sleeping at age fifteen is nothing like sleeping at age forty.”

Moments later something louder and more ferocious than the crash woke me up. The head dorm counselor arrived on the scene. Yehiel Kalish. He had the waking power of all other dorm counselors combined. His voice could pierce eardrums like an arrow through a balloon. A man born to yell.

“EVERYONE OUT OF THE BUILDING! EVERYONE OUT OF THE BUILDING!”

He shrieked on repeat like the most terrifying alarm you’ve ever heard. His dangerously loud voice echoed off every inch of concrete, amplifying its power. For a moment my eyes opened in the dark dorm room as his screams reverbarated. Confused thoughts scampered across my mind like spooked chickens. A dozen of them hit in one instant. A fire? A prank? A bomb? What time is it? Parshat Zachor?

I forced my eyes towards my alarm clock to check the time. 5am, about the earliest I had ever awoken in my life until that point. The screaming didn’t stop. A moment later I noticed the emergency lights flashing beneath my door and heard the commotion of people fleeing in the hallway. I stopped thinking, jumped out of bed, and jolted out of the room.

Thankfully, the stairwell was right there, so I didn’t have to go far. Half-sleeping kids, sluggish and frightened, trampled down the stairs. The people in front of me said we needed to go to the Beit Midrash, a small building marked by a golden dome and a menorah adjacent to the main building dedicated to prayer service and talmudic study.

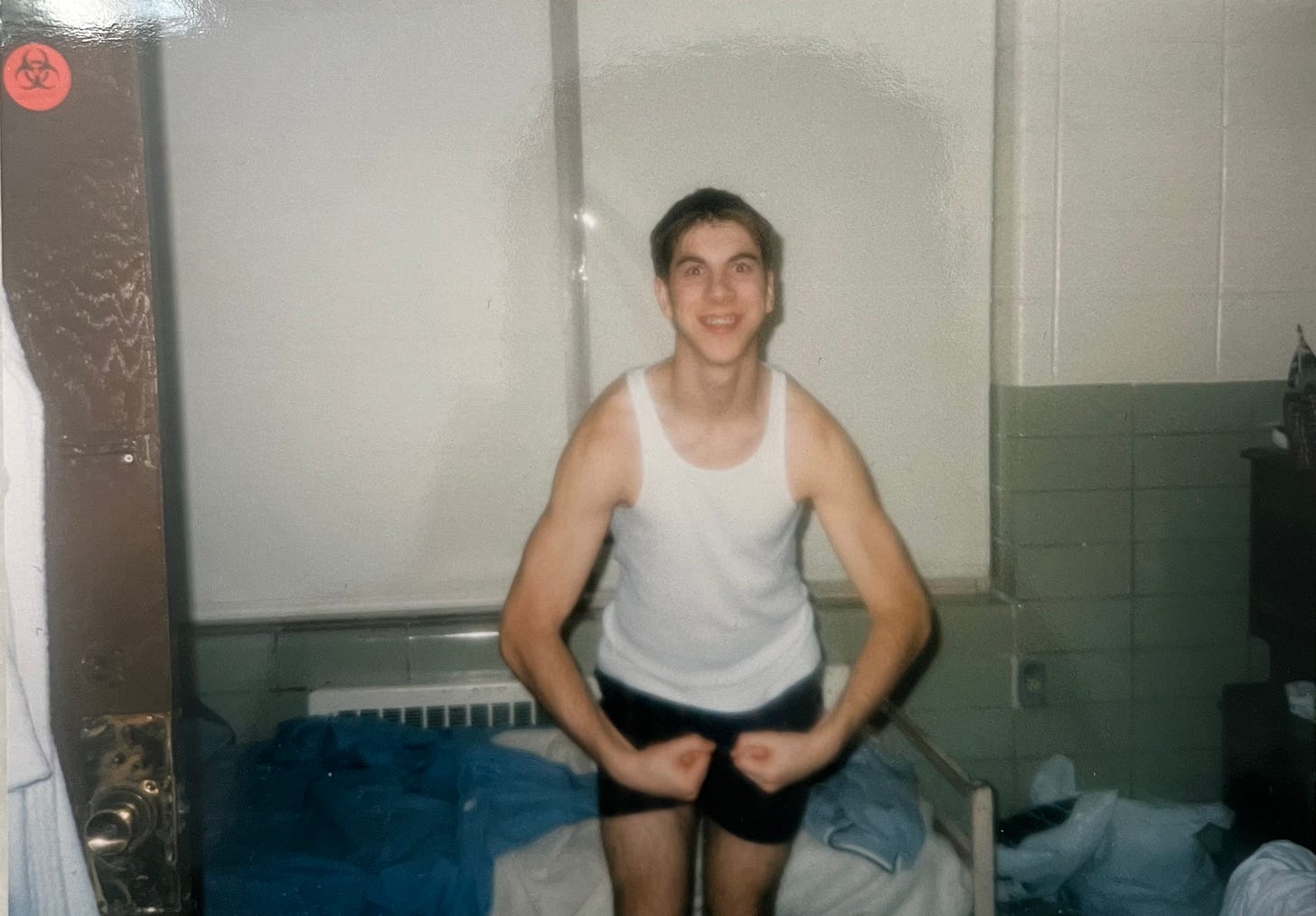

I walked out of the building into the forty degree chill and freezing rain, which would have been snow if it were just a few degrees cooler. The sensation of cold wetness across my body shocked me into the realization that I only wore boxers and a “wife beater.” (A relic of a term that I do not use with intentions to offend, but that suits the era and the narrative. Forgive me.)

I entered the Beit Midrash to find that everyone else either slept in very different clothes than me or had taken their time to put on something more substantial—hoodies, sweatshirts, flannels, sweatpants, flip-flops, slippers, shoes, sandals, bath robes, and other types of warm apparel. Then there was me: beater and boxers.

Here’s the thing about sleeping alone. The privacy and personal space are wonderful, but should you ever find yourself in an emergency, fighting for survival, the additional input or collaborative problem solving of a friend certainly come in handy. I presume this is why everyone else found the wherewithal to don warm clothing and I simply sprinted outside in the freezing rain in my underwear. As my friends and I began to recognize the humor in this situation, I figured the joke would be short-lived once I found my way back inside to recover any form of wardrobe.

A few minutes later the head dorm counselor entered the Beit Midrash with the last of students from the dorm. He gathered everyone together and explained (in a much more moderate volume) that lightning struck the building’s chimney. He said the fire department was en route and that we were going to stay put until they got there and await their instructions. I asked if I could quickly run inside and get some clothes. He said that it was not safe and no one was allowed in until further notice.

It started to rain a little harder now. After about twenty minutes, the head dorm counselor said that we could not go back into the building and that everyone was going to walk to the gym at Hillel Torah, the elementary school across the field behind the Yeshiva. I held out hope and decided to stay behind in case someone changed their mind about me getting real clothing. The rest of the people in the Beit Midrash walked down the alley to Hillel Torah.

After a very short wait, one of the firemen came to tell me that there was no way I could go into the building. It was condemned and could collapse. While this seemed highly unrealistic to a lightly-clothed, moderately wet, and fairly freezing fifteen year-old, his position seemed resolute.

I looked out of the Beit Midrash window and saw the steady flow of rain blanketing the terrain. The other kids approached Hillel Torah. Approached safety. (Some even had jackets or umbrellas, as if taunting me). I had nothing but a half-empty tank of willpower. I needed to catch up or be left behind. So with a deep breath, I opened the Beit Midrash door and sprinted across the field in the freezing rain like like a Tough Mudder obstacle.

The field was about one hundred yards long. For the first third of the journey, I felt the wet, slushy, muddy grass squishing below my feet with every stride. The ground squelched between my toes. My eyes squinted to keep out the rain as I tried not to think about how much further until I caught up.

Then it all went numb; toes, feet, face, brain. I saw the line of kids walking single file and as they noticed my sprinting across the field in my underwear. Their laughter didn’t impact me slightly. In fact, I instantly realized the absurdity of the scene and laughed with them (in my head, as my frozen face failed to emote). I made it to the gym just as the last few kids walked in. Moments after I made it inside, the rain stopped.

My old classmate, Mendy Mark, described the scene as follows (Credit: HTC Centennial Video):

Once inside, I felt relieved. But something seemed off. My heart rate settled down and I caught my breath, but the sense of cold permeating my being didn’t ease. I soon realized why. The school did not run their heat in the empty building over the weekend. It became clear that this was merely another stop on our journey, not the destination. I needed to get warm, so I started exploring.

Luckily, I knew the Hillel Torah gym well. I played basketball there a few times per week, often finding ways to sneak in during the day and prop the door open so my friends and I could play in the evenings. (Poor security – another relic of the 90’s.) Because of this, I knew where to find the lost-and-found box.

Finding an entire wardrobe for a 6”2 adolescent in a Jewish elementary school lost-and-found was a low-probability endeavor. But after working my way through a few Power Rangers lunch boxes, slap bracelets, and Spongebob t-shirts, I struck gold: An XL Adidas zip-up, a pair of black sweatpants that went most of the way down my shins, and two unmatched tube socks that fit enough to cover my feet. Warmth! Finally!

I joined the clothed people, feeling like one of them all along—like I belonged. But they saw through my shabby rag-tag attire and continued to playfully mock me while I marveled at my own ingenuity. Shortly after, we got the next update from the head dorm counselor. He confirmed that we could not stay in the school because there was no heat. The plan, he said, was for students to walk to their friends houses, who mostly lived within an hour walk, for the remainder of shabbat. Anyone who didn’t have anywhere to go could join a group walking to a local Rabbi’s house ten minutes away.

While I solved the warmth problem, I still didn’t solve the shoe problem. Without shoes, I couldn’t really go anywhere. But there was no chance I was going to find a pair of size 13 shoes anywhere in that school. So I searched for another plan and began rummaging through the gym. In one of the closets I found a set of hockey pads, which I figured I could use for shoes. I strapped the goalie shin guards to my feet and took a few practice steps. Sufficient. I determined that the best next-stop would be the Rabbi’s house where I hoped to find real shoes.

I got to the Rabbi’s house around 8am. The foam padding on the hockey pads saturated with freezing puddle-water and the straps barely held on to my feet. As I went inside, I left the pads on the front steps and took off my soaking socks. I sat down on his couch and enjoyed the first true taste of central heat in a few hours.

As I settled in, I realized that spending 10 hours (the remainder of Shabbat) at the Rabbi’s house without friends was not the cool or fun thing to do, and so like any fifteen your old worth his salt, I worked on my way out. I asked the Rabbi if he had any shoes or socks I could borrow so I could walk to a friend's house. He gave me two pairs of socks and he found an old pair of size 11 dress shoes in his closet. I said they would be fine. I asked him for a few plastic shopping bags for the road.

As I tried to cram size 13 feet into size 11 shoes he asked me if I was sure I wanted to leave. I reassured him that I would be OK and showed him that I could wear the shoes like slides, with my heels over the backs of the shoes. This assuaged his concerns.

As I left his house, I grabbed the hockey pads and put them in a bag. After painfully walking far enough to be out of sight, I initiated my MacGyver brain and refashioned an upgraded version of the hockey-pad shoes. First, I wrapped my feet in a plastic bag to keep my socks dry, then I took the shoelaces from the shoes and used them to better secure the pads to my feet, and then I took the extra bags and put them over the hockey pads for an extra layer of protection. I discarded the shoes and resumed my journey.

I walked for an hour and twenty minutes down Touhy Ave., one of the busiest streets in Skokie. A homeless child. Sweatpants riding my shins. A baggy sweatshirt and no jacket. Plastic bags and goalie pads for shoes. The outer bags lasted about a few blocks before shredding. The looks I got from my friends as I sprinted across the field in my underwear could not compare to the looks I got as I walked down Touhy Ave. dressed like this. But I just kept my eyes on the wet ground in front of me and took it one step at a time.

I arrived at my friend's house just in time for shabbat lunch. I told her parents the story of the lightning strike and my daring escape. I am not sure if they were speechless or just quiet folks, but I don’t remember talking about it for too long. Soon they served a hot cholent (a traditional hot stew served at Shabbat lunch) and I felt just right, as if none of it had ever happened. As if I had been warm and safe all morning.

The next day I took a train home to Minnesota, which felt unbearably long without any of my CDs. (But, alas, there was a time when we survived without smartphones!). I spent Purim there as the school figured out how to remain open while the building was condemned. In the weeks ahead I fought through cases of pneumonia and bronchitis. The building remained closed for over a month and we took classes at a makeshift setup in a local synagogue, often sneaking out during the days to watch March Madness at friend’s houses.

As time passed, some of the rabbis sought explanations as to why lightning struck our school on Parshat Zachor. Was there divine meaning in it? Was it a sign? A punishment for the kids who did not follow the rules? In the twenty-five years since the lighting struck I can think of only one reason that this event took place: to give us an incredible story.

My kids loved this article. “Man born to yell.” Classic. Hope you are doing well Ross. Loved that photo.